Catastrophe (Issue 01: 15) “Jacqueline Springer and Rodney P Get Real about the Grenfell Tower Crisis”

Catastrophe met with UK hip-hop artist Rodney P and professor and broadcast journalist, Jacqueline Springer, to discuss the social issues surrounding the Grenfell Tower Crisis that were not mentioned in the mainstream media. Click through the images above to read the interview in it’s original print layout or see the typed transcript below.

Interview transcript:

On June 14, 2017, a catastrophic fire broke out at Grenfell Tower, a twenty-four story public housing project located in North Kensington, West London, where at least seventy-nine people died or went missing and hundreds more were left homeless. The tower was home to primarily low-income residents, many of whom immigrated to the U.K, but the building was located nearby a famously affluent neighborhood. If not due to the government’s decision to remodel the building as a beautification project, using flammable cladding to cut construction costs, and their neglection of resident complaints about the jeopardy of the tower, the crisis could have been preventable.

For years before the fire, residents raised concerns about the issues in the tower. The residents weren’t only ignored, but also systematically silenced by the government. It’s clear that a change of culture within public institutions is necessary for the equal treatment of those living in social housing.

Catastrophe met with UK hip-hop artist Rodney P and professor and broadcast journalist, Jacqueline Springer, to discuss the social issues surrounding the Grenfell Tower Crisis that were not mentioned in the mainstream media.

Springer: Do you remember the morning, waking up to the news?

Rodney P: I drove past the building at night, I actually saw it burning and it was quite surreal. You’re coming over the west way so you’re not on the road next to the building. I had distance. At first, it’s like wow, it’s on fire. It’s a spectacle, but then you realize that means people are dying. I never assumed that it would’ve been as bad as it was. You just never imagine that they’re going to be telling people to stay in their houses when they’re burning down. You just don’t imagine that. But when I woke up the next morning, I actually realized what happened, and how bad it was. It was disgusting and frightening because you know no one gave a fuck about anyone on that block. No one who could’ve saved them cared about them. And so here we are, it’s the day after and people still don’t care, and there are lots of blocks in London. So now you’re living in fear, thinking well I know a lot of people who live in tower blocks that look just like that. It was horrendous, truly horrible. It’s in a part of London where I have a lot of friends, where I know that part of London to be a community. And there aren’t many communities left in London, to be honest, not in the way they were. But that piece of West London was a community, and that would’ve gutted it right in the middle.

Angela: In the area, there were a lot of posters up about anti-racism community talks, and I think there was an Angela Davis event poster as well.

Rodney: But a lot of the stuff in that area would’ve pre-dated that anyway. That area of West London is very much geared like that. It’s very multicultural there, there’s a lot of immigrants there, and the community has been there forever. A lot of those posters and a lot of that mentality already existed in that area. As I said, there aren’t that many communities like that left in London. London used to be pockets of communities, but they’ve all been torn down, stripped out, and gentrified. And I’m curious to see what happens afterward. This disaster seems to be a good excuse to move out the people who have been there and move in a new set of people. And West London is some prime property, I’m not saying there was any conspiracy in the burning of the tower, but I don’t trust any of them. I believe they would use anything as an excuse to forward their own agendas.

Angela: Do you think that the attention that was already building up in Kensington that predated the burning of the tower, as well as the problems of racism in that area affected how the community and all of Central London responded to the crisis?

Rodney: I don’t know how other people reacted, but I know within my circle and within the young people that I know, it felt like racism and it felt like no one cared about the people who lived in Grenfell Tower. The real anger is in the voice of the young people. When I look at the national coverage of it, it was obvious that it was a disaster but I don’t think you got the real sense of betrayal, anger, and fear that is left within the community. There’s no trust, and this gives us another reason to say we don’t trust these people...because of what they’ve done. I think the fact that that building was clad in that bullshit material was very much about saving a few pennies, and making sure that the rich part of West London doesn’t have to look at an eyesore, so let’s make it look as pretty as it can, for as cheap as possible. That’s what caused Grenfell, people not really caring and not wanting to lose out of their pocket, and not wanting to be bothered with these “grimy, low immigrants.” That was the attitude, and I didn’t see much of that reality and truth being expressed in what came afterward. I didn’t see that. But then you hear someone like Stormzy talking about it, that’s where the young people want to air their grievances. The establishment might not take that well, but those are the voices that need to be heard and those are the voices that need to be at the front and center. That representation of how people felt should’ve been front and center, because that’s what was real and if we don’t latch on to what people really think and feel, then we just repeat the same shit again. People don’t care, all they care about is covering their tracks, but the people are wise to that and those types of liberties won’t be allowed to stand.

Josie: Are there any artists that inspire you who have made a difference in the way Grenfell Tower crisis was perceived in the media?

Rodney: I put on an event soon after to try and raise some money to help. We did an event in Brixton, and pretty much everyone I asked to come in UK Hip Hop came. So in terms of mobilizing people, after the fact it was very easy because people wanted to get involved. You know, Stormzy was on the Brit Awards so he had the national spotlight, but I know that there are a lot of artists that speak about Grenfell every day, and that disaster has been a motivation for a lot of incredible art that came out of it. Rappers, poets, singers, photographers have used that disaster as a motivation to make some amazing things, and that has to be a blessing. But they don’t have the national spotlight, and we need to be able to express exactly how we feel in our own voices, nationally for everyone to hear. We need those outlets but they don’t exist, and that’s a shame. But the outlets that do exist within the community, within pirate radio, poetry jams, hip-hop jams, MC cyphers... those emotions are definitely being expressed a lot. I think it’s a shame that it takes so many people died in that way, but it does pull communities together and it shouldn’t have to be that. All the things that exist to create the burning of Grenfell Tower, you can’t tell me it was a secret. The were no secrets, they knew what they paid for. There have been other fires in London to a lesser degree, but it’s the same thing happening. So they know what it was, but they didn’t care enough to go out and look out for these people and make sure they are safe in their homes. I think it’s disgusting and you just can't trust anyone…you can trust them but you can only trust them to do what you make them do. We have to trust ourselves and be staunch enough to demand what we deserve. I think that attitude is coming, and the young people of the day–as much as they are accused of being lost–I think a lot of the young people are meeting much more socially and politically and I’m just aware of the blocks being put up in front of them to stop them. These young people now are using technology and their educations to find new ways to navigate all of that bullshit, and they are finding their own paths to success...and that has got to be good.

Springer: I think there are two things that we need to think about in the traditions of how disasters and catastrophes that were avoidable, and disasters that lead to fatalities on such a large level. Personally, I believe more people died than 76 people died in the burning of Grenfell Tower.

Rodney: So do I! I have friends who were firemen in that building, who would say that they would go into a room and just see a mass of melted bodies, that they couldn’t identify. Because this building is full of immigrants, they aren’t legal here, and they have no paperwork, so they just did not exist. I think that even that is a disrespect, the fact that they didn’t come out and say we had this many people that we can identify, but we know there were more people in that building. The fact that they did not say anything...it’s disgusting. Somewhere, someone’s mother is thinking, well my son went to England and he just never came home, and he’s just not accounted for. Why can’t people just do the right thing, rather than protect yourselves and your mess up? Just do the right thing...but that’s easier said than done.

Springer: This is about honesty. There is a subdivision of it and there’s a level of self-protection, there’s a deck of cards, that if someone whistle blows on something, somebody else falls. I think what we’re looking at here is class prejudice, you’re also looking at identity politics, racism, jingoism. The whole idea that, if people were living in that block and they had people there that weren’t supposed to be there, then well that’s kind of what you get. No, you should not die because of that. That also shouldn’t temper your feelings about whether you have sympathy for someone who was burned to death. People do things to circumnavigate the law, not always, but a lot of the time, because if they were to adhere to the law, there would be a bigger problem. Somebody could have gone over to a person’s apartment that night, because you do, “come over to mine we’ll Netflix and chill.” Somebody else could’ve been there, but if you deduct the amount of known residents from those who survived, those were injured, and those whose bodies that you cannot identify, there are strategic ways journalistically that you can look at the way that Grenfell and the story of Grenfell rolls out. And so you go through this enormous shock that happened, and when the lead story was running for 48 hours, people go, okay, this building is on fire, but fires happen around the country. There’s a real sort of disassociation because of geography, then there is a sense of boredom with it, and you’re exploiting the tragedy, but you need to re-tell this story. In those 48 hours, more and more people who survived and lived in that area were telling the newspapers that this was not just about a fire that took place. This was about something that happened that could have been preventable and should have been preventable. But they weren’t listened to. Had not for this blog that existed, there would be no kind of proof for this paper trail. Where, by residence, some of whom died in that fire. Where, by residence, some of which had pointed out and forewarned what had happened. So, that comes down to whose voice matters most. That comes down to class, that comes down to your national identity. You’re not even a citizen here, you’re still awaiting.

Rodney P: Mhm, English is still a second language to you so why are we listening anyway? That’s the issue.

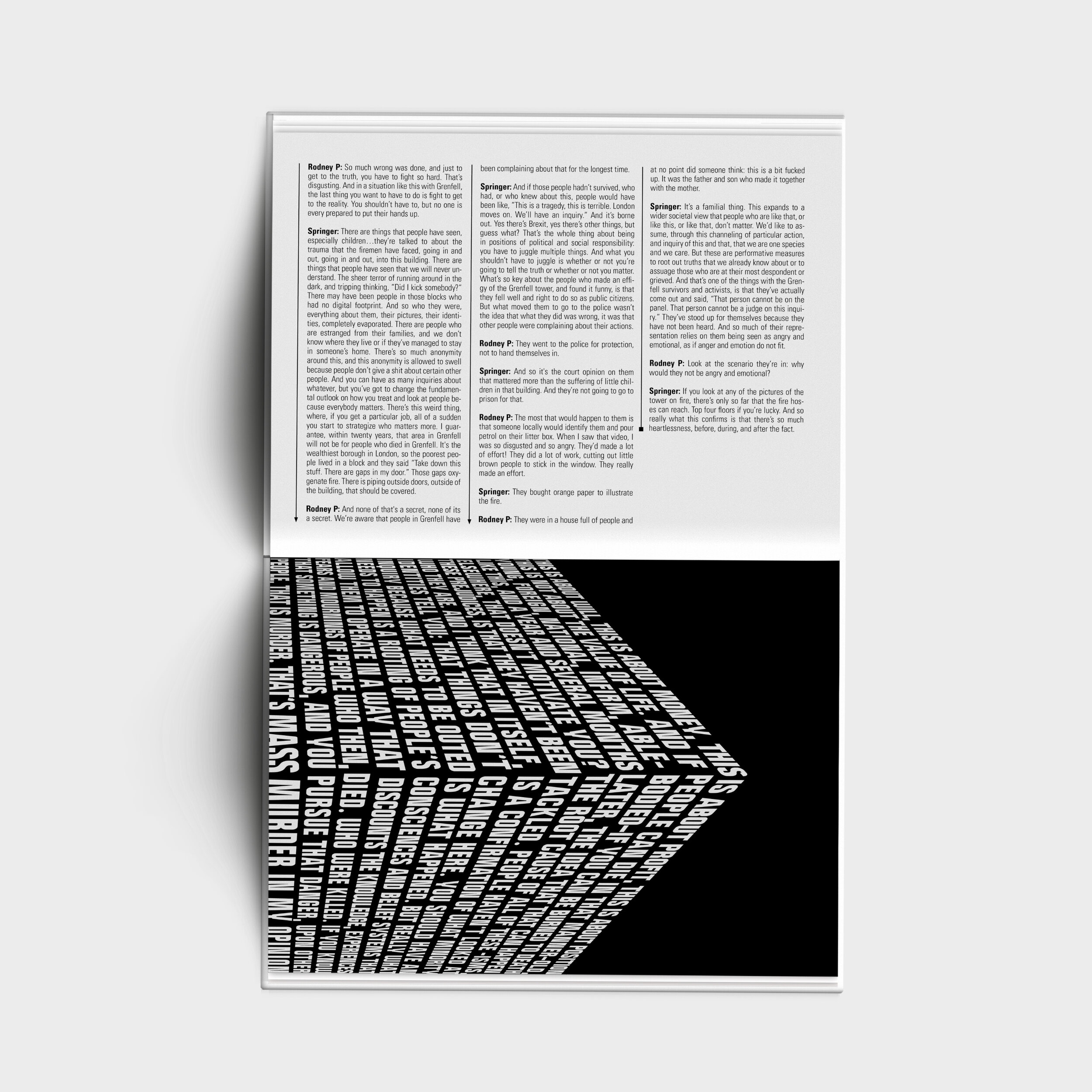

Springer: So the value of people even in life...they’re not listened to, in death, they’re unaccounted for. Their numbers, as far as I’m concerned, are simplified. But also, there are strategic ways in which this country operates. So when something occurs that should not, an inquiring has to happen. And the length of time that that inquiry took allowed the strong sentiment that was expressed. The fear of many people to be dissipated by other pervading issues. So what you have to do is count in the sheer horror of what people are seeing, by this cultural need to know what is being seen that something is going to be done about it. But when people were asking what was happening, so many of those survivors said the fire went up, up, the building. Well, it was almost like, how could it have gone up the building because concrete doesn’t burn in that way? They weren’t listened to. There’s footage of an interview with some survivors on Newsnight and Emily Maitlis is shushing, she’s batting her hand down on somebody who was talking over somebody who was being interviewed. And that woman said, “there is a blog” and from there on in, more people started to dig up on this. People are not listened to because of their identity, on a number of different criteria: their class identity, their national, their gendered, their regional identity. And what you have in Grenfell, is a coalescence of that contempt. This notion that people that are employed know better than people that are living there. This kind of pillaring of the man whose home the fire took hold of–he’s of this origin–as if his origin has anything to do with what had happened! What happened was that people burned to death, and people went up onto the roof, a helicopter came. The intensity of that heat was so great that the helicopter could not go anywhere closer. And those people would have thought, I’m sure, “we’re gonna be okay.” There were people running out of that building and it had no interior sprinkles. They were running down the stairs that had no interior lighting. They were tripping over people who had succumbed to smoke inhalation. If you told your babies who can walk to hold onto each other, but you can’t see what you’re running down…the sheer enormity of everything. At this stage, as a professor, I can’t even teach about this. I didn’t even know anybody there. I can’t teach about this with any subjectivity. It upsets me so very profoundly...and I look at some horrible shit. But honestly, that was mass murder right there. And I think, more than anything else, we come for ourselves with the idea that we can move on, that we have a real sense of community, when what has not changed is that people feel that the value of other people, because of their social categorizations, that that is enough. But there is something about you, and the way you view people, and that level of suffering, which was publicly displayed, that tells you something about the way in which other people's’ lives and the manner of their deaths are not valued. And that tells us something about this country: it tells us about the way in which, even now on November 26th, there are several blocks in this country that still have not had that cladding removed.

Rodney P: Mhm, and that’s got nothing to do with anything except who is going to pay for it.

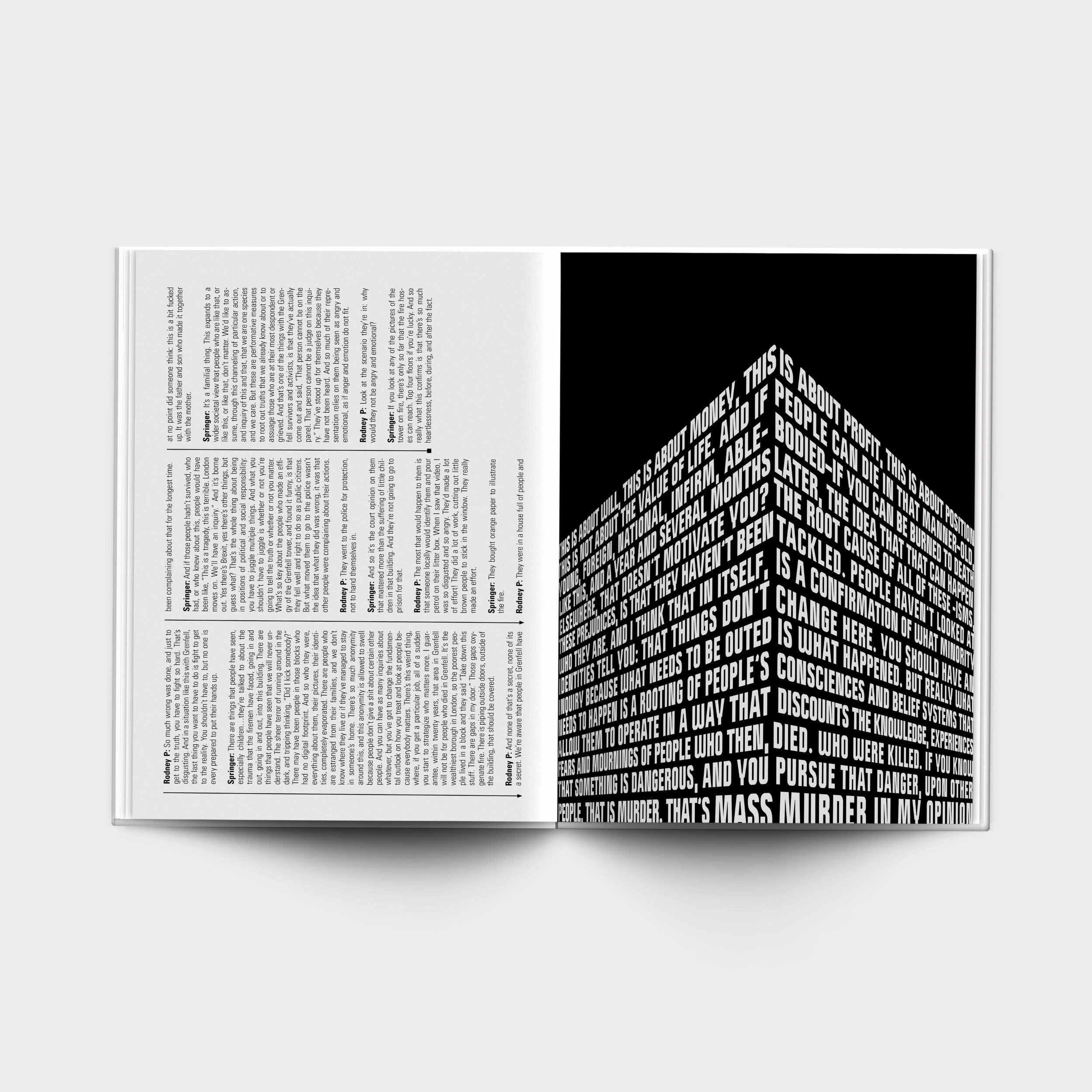

Springer: This is about will, this is about money, this is about profit, this is about position. This is not about the value of life. And if people can die in that manner–old, young, foreign, national, infirm, able-bodied–if you can be burned to death like this, and a year and several months later, the idea that that can happen elsewhere, that doesn’t motivate you? The root cause of all of these -isms, these prejudices, is that they haven’t been tackled. People haven’t looked at who they are. And I think that in itself, is a confirmation of what minority identities tell you: that things don’t change here. You should have an inquiry because what needs to be outed, is what happened. But really what needs to happen, is a rooting of peoples’ consciences and belief systems that allow them to operate in a way that discounts the knowledge, experiences, fears, and mournings of people who, then, died. Who were killed. If you know that something is dangerous, and you pursue that danger, upon other people, that is murder.

Rodney P: That is murder.

Springer: That’s mass murder in my opinion. And, as a result of that, I cannot teach on this topic. We seek comfort in the way in which people pay tribute, the way that they show that there is value, that we show respect for the survivors and their activism.

Rodney P: So much wrong was done, and just to get to the truth, you have to fight so hard. That’s disgusting. And in a situation like this with Grenfell, the last thing you want to have to do is fight to get to the reality. You shouldn’t have to, but no one is every prepared to put their hands up.

Springer: There are things that people have seen, especially children…they’re taught about the trauma that the firemen have faced, going in and out, going in and out, into this building. There are things that people have seen that we will never understand. The sheer terror of running around in the dark, and tripping thinking, “Did I kick somebody?” There may have been people in those blocks who had no digital footprint. And so who they were, everything about them, their pictures, their identities, completely evaporated. There are people who are estranged from their families, and we don’t know where they live or if they’ve managed to stay in someone’s home. There’s so much anonymity around this, and this anonymity is allowed to swell because people don’t give a shit about certain other people. And you can have as many inquiries about whatever, but you’ve got to change the fundamental outlook on how you treat and look at people because everybody matters. There’s this weird thing, where, if you get a particular job, all of a sudden you start to strategize who matters more. I guarantee, within twenty years, that area in Grenfell will not be for people who died in Grenfell. It's the wealthiest borough in London, so the poorest people lived in a block and they said “Take down this stuff. There are gaps in my door.” Those gaps oxygenate fire. There is piping that they’ve put outside of the block, outside of the building, that should be covered.

Rodney P: And none of that's a secret, none of its a secret. We’re aware that people in Grenfell have been complaining about that for the longest time.

Springer: And if those people hadn’t survived, who had, or who knew about this, people would have been like, “This is a tragedy, this is terrible. London moves on. We’ll have an inquiry.” And it’s born out. Yes there’s Brexit, yes there’s other things, but guess what? That’s the whole thing about being in positions of political and social responsibility: you have to juggle multiple things. And what you shouldn’t have to juggle is whether or not you’re going to tell the truth or whether or not you matter. What’s so key about the people who made an effigy of the Grenfell tower, and found it funny, is that they fell well and right to do so as public citizens. But what moved them to go to the police wasn’t the idea that what they did was wrong, it was that other people were complaining about their actions.

Rodney P: They went to the police for protection, not to hand themselves in.

Springer: And so it's the court opinion on them that mattered more than the suffering of little children in that building. And they’re not going to go to prison for that.

Rodney P: The most that would happen to them is that someone locally would identify them and pour petrol on their litter box. When I saw that video, I was so disgusted and so angry. They’d made a lot of effort! They did a lot of work, cutting out little brown people to stick in the window. They really made an effort.

Springer: They bought orange paper to illustrate the fire.

Rodney P: They were in a house full of people and at no point did someone think: this is a bit fucked up. It was the father and son who made it together with the mother.

Springer: It’s a familial thing. This expands to a wider societal view that people who are like that, or like this, or like that, don’t matter. We’d like to assume, through this channeling of particular action, and inquiry of this and that, that we are one species and we care. But these are performative measures to root out truths that we already know about or to assuage those who are at their most despondent or grieved. And that’s one of the things with the Grenfell survivors and activists, is that they’ve actually come out and said, “That person cannot be on the panel. That person cannot be a judge on this inquiry.” They’ve stood up for themselves because they have not been heard. And so much of their representation relies on them being seen as angry and emotional, as if anger and emotion do not fit.

Rodney P: Look at the scenario they’re in: why would they not be angry and emotional?

Springer: If you look at any of the pictures of the tower on fire, there’s only so far that the fire hoses can reach. Top four floors if you’re lucky. And so really what this confirms is that there’s so much heartlessness, before, during, and after the fact.

-

It is estimated that 56,000 people are still living in buildings wrapped in the same flammable cladding as the Grenfell Tower. Click here to sign a petition tho ensure London’s public buildings are safe, that the government invests in fire protection and reform London’s fire and building safety systems, to ensure that a fire like the Grenfell Tower tragedy never happens again.